Training and dedication to quality improvement goals regarding the provision of excellent BLS care are essential for establishing a baseline from which survival can continue to be improved. When excellent basic care is provided by all systems, the wide variations in survival that now exist may be reduced. This will allow a clearer baseline from which the survival impact of additional therapies can be evaluated in the future. Ensuring that high-quality CPR is provided in an EMS system can be approached in a number of ways.

Ongoing evaluation of CPR metrics from SCA cases can provide a quality check on interruptions to compressions, pause times around defibrillation, and other CPR metrics. Implementation of regular training scenarios using manikins that provide feedback on the rate and depth of compressions can be used to improve skills and reduce pause times. Each system should establish a method for ensuring that high-quality CPR is provided as a basic requisite. The Appendix contains a sample review form for CPR Metrics.

While drugs and devices have a place in resuscitation, there is no substitute for excellent basic care.17 High-quality CPR and early defibrillation are the best tools EMS owns, and the important role of the first responder in delivering this important treatment must also be recognized.

Pit Crew Resuscitation

There has been a fair amount of enthusiasm generated around the concept of Pit Crew Resuscitation.

Popularized by Wake County EMS and Austin Travis County’s charismatic EMS medical directors, Pit Crew Resuscitation is a highly coordinated, well-rehearsed delivery of excellent basic resuscitation care, accounting for human factors principles and emphasizing the attention to all details of good basic resuscitation skills.

While several configurations have been suggested for choreographing the care of the SCA victim, it is important to remember that the goal is to provide excellent basic care in a consistent manner.

Having a blueprint of predetermined responsibilities for each crew, complete with instructions about where to position oneself can be very useful. But it is not only about assigning roles and expecting performance from the pit crew. EMS professionals recognize that there are unending possible configurations of response to out of hospital arrests, and that the nature of these calls is always highly chaotic and rarely the same as the previous case.

There is a need for flexibility, and a necessary ability to work with whatever resources turn up. Cooperation between agencies is a key concept, the best interests of the patient are only served when territory is not an issue between responding agencies. The ability to work and train with other providers in an effective and efficient manner is the skill that distinguishes EMTs, paramedics, and their agencies in this environment.

Goals

Remember that the goal of having a pit crew approach is to ensure that all priorities are focused upon. The system used should be continuously reassessed and changes made when necessary.

- Limit interruptions to compressions

- Control ventilations

- Defibrillate in a timely manner

- Ensure that compressions are not being given by someone who is fatigued

Training

Training with other responder agencies is essential to ensure that all providers are prepared to work together effectively. In Austin, EMS providers went to the simulation lab to work out the best way to work with their resources.

Below is one pit crew configuration incorporating 5 leaders:

Pit Crew Leader: One who supervises and assigns roles, monitors time, manages crowd control and does not perform patient care duties.

Airway Leader: One who makes airway decisions, performs appropriate airway procedures, communicates with family as needed completes PCR at the hospital.

Medication Leader: One who defibrillates, inserts IV or IO, administers or supervises medication delivery, tracks monitor changes.

CPR Chief: One who supervises and performs CPR, assists with medication and equipment setup and performs communications.

Team Assistant: Assists with CPR, communications and equipment setup.

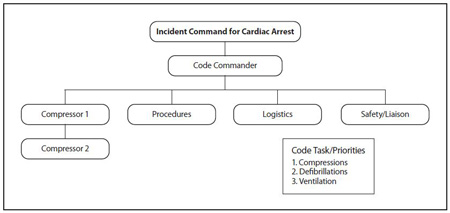

The Chicago EMS and Chicago Fire Department – Incident Command System in Cardiac Arrest Care

The Illinois HeartRescue partners have instituted an incident command system as a tool to address leadership, teamwork and communication challenges in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest care. Incident command systems can provide accountability, improved communication, an orderly planning process, a flexible yet predesigned management structure, as well as a method to integrate interagency requirements into management structure. These are all qualities needed during a well-run resuscitation call

The Illinois Incident Command for Cardiac Arrest (ICCA) model is adaptable to various compliments of manpower and works with a multi-agency response. The versatility of the ICCA model is guides all providers to focus on key code task/priorities that are all al the BLS level. Role assignments are given based on available manpower present in order of code tasks/priorities, regardless of the level of training or certification.

Roles

In this model, the following roles are established by first arriving personnel in order to ensure code priorities:

Code Commander: The person in charge, usually one of the first on scene. May also be needed to complete code tasks, and as more providers arrive, may remain in command and delegate tasks. Code Commander assesses scene and requests additional resources as needed.

Compressor #1: Charged with performing the first 2 minutes of uninterrupted high-quality chest compressions; may provide early defibrillation as indicated.

Compressor #2: Acts as a coach for Compressor #1 using available monitor data, PETCO2 levels and relieves Compressor #1 after 2 minutes of CPR.

Logistics: This position can be added if there is additional manpower on scene; responsible for medications and equipment, including cot preparation for transport when indicated.

Liaison/Safety: Responsible for controlling the scene. Interfaces with bystanders, documents code record and assists with family need.

Tasks

The code tasks/priorities include:

- Provision of uninterrupted, high-quality chest compressions at a rate of 100 beats per minute, sharing this responsibility to prevent rescuer fatigue.

- Provision of early defibrillation without interrupting or delaying CPR during application of pads or charging.

- Provision of controlled ventilatory management during cardiac arrest. Advanced airway placement is deferred until chest compressions (priority #1) and defibrillation (priority #2) are satisfied. Ventilation rate is 8 per minute. ETCO2 is mandatory for confirmation of tube placement, monitoring chest compression quality and for watching for ROSC.

Training

In Chicago, the training for the ICCA session includes a one hour didactic and video session. A separate three-hour hands-on rotation through the CFD simulation training center allows small group scenarios to be enacted. Video debriefing is used for performance improvement. A companion ICCA course for dispatchers, ICCA-EMD, emphasizes the importance of rapid recognition of cardiac arrest, pre-arrival instructions on chest compression-only CPR and increased awareness of manpower and resources for in-field EMS providers delivering cardiac arrest care. This course also provides strategies and techniques to help address bystander uncertainty, panic, fear, poor confidence, concern for liability or causing harm, and reluctance to perform mouth-tomouth. Through video, audio and simulation, ICCA-EMD emphasizes the critical role emergency 42 telecommunicators have though the bystander and EMS links in the chain of survival. A CQI component is currently underway using monitor defibrillator software, capnography and cardiac arrest survival statistics including survival to hospital discharge.

EMS Use of CPR Devices

The American Heart Association has published Highlights of the 2010 AHA Guidelines for CPR and Emergency Cardiovascular Care, which includes statements addressing the use of CPR devices. The statements can be read in their entirety in the highlights document available online. Regarding the use of CPR devices, the summary statement from the AHA 2010 Guidelines Part 7. CPR Techniques and Devices states “To date, no adjunct has consistently been shown to be superior to standard conventional (manual) CPR for out-of-hospital basic life support, and no device other than a defibrillator has consistently improved long-term survival from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. A variety of CPR techniques and devices may improve hemodynamics or short-term survival when used by well-trained providers in selected patients. All of these techniques and devices have the potential to delay chest compressions and defibrillation. In order to prevent delays and maximize efficiency, initial training, ongoing monitoring, and retraining programs should be offered to providers on a frequent and ongoing basis.”